By Mikael Böök

>> In comments below watch and listen to the very first musical act on this blog

As I previously told in this blog, I joined IFLA last summer as a personal member. Thus I had the opportunity to follow IFLA’s recent General Assembly meeting . IFLA’s General Assembly met in The Hague on 5 November. The meeting took place in the wake of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. I did not find out how many members were in den Haag, only a few I would think. Many more probably followed the meeting like myself, over the internet. In order for the votes to go smoothly, voting by proxy was allowed. The agenda had been reduced to a minimum, the main thing was to decide on the mandatory items and to award some annual honors. In addition, it was decided that IFLA will hold an Extraordinary General Assembly (in Melbourne, Australia on 12 February 2021) to decide on the adoption of new IFLA Statutes.

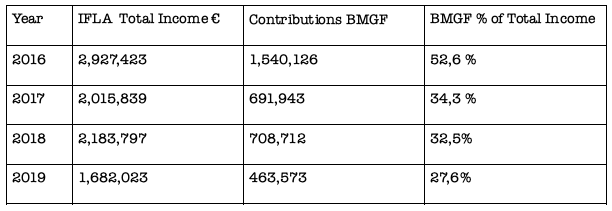

As a novice in this context, there was one thing in particular that I focused on and to which I will now devote a few lines, namely the operating grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The treasurer’s report showed that IFLA’s expenses in 2019 were € 1,654,982 compared to € 1,892,860 in 2018. The difference € 237,878, it was explained, was mainly because the IFLA Global Libraries Foundation covered the costs of the International Advocacy Program (IAP) in 2019 with € 245,139.

For me, this raised the question: what is the Stichting IFLA Global Libraries?

On IFLA’s webpages we learn that …

… «the object of the foundation [Stichting, in Dutch], which is exclusively charitable and educational, is to strengthen the library field and to empower public libraries to improve people’s lives and support growth of sustainable societies» and that it is financed through donations, grants, income from the foundation’s own activities etc. The foundation’s board has a chairman and two appointed board members as well as a general secretary.

The composition of the board and the descriptions of the board members’ backgrounds suggest that it might not be entirely wrong to call the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) and the IFLA Global Libraries Foundation merry bedfellows. It thus seems to be the case that the latter has been founded in order to be able to conveniently channel money and influence from the former to IFLA.

This impression was significantly strengthened when I studied the annual accounts of IFLA’s finances over the past four years. These are found at Ifla.org. To get an overview, I compiled the following table:

The Stichting IFLA Global Libraries has an own website with information about the current three board members and the general secretary. They are:

Glòria Pérez-Salmerón, who was IFLA’s chair 2017-2019. She has previously been head of Spain’s National Library.

Deborah Jacobs, who has led the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Global Libraries initiative since 2008 and was named an honorary member of the IFLA during the 2019 Athens World Conference.

Inga Lundén, former chair of the Swedish Library Association and long-time director of Stockholm City Library. It is mentioned in her description that the BMGF and Global Libraries have been a «source of inspiration» for her in her activities as a mentor and advisor to the International Network of Emerging Library Innovators (INELI).

Gerald Leitner, the General Secretary of the Stichting IFLA Global Libraries. He is also the Secretary General of IFLA. Leitner has previously led the Austrian Library Association and EBLIDA, the librarians’ lobby in the EU. In 2017, Leitner launched the Global Vision project, which aims to build a new strategy for IFLA «from scratch.»

Many of us must have noticed that Bill Gates and Mrs. Melinda, through their BMGF and its huge capital, exercise a significant influence in the present world. But who could have guessed that they have taken such a firm grip on the entire global library development?

Well, at least we who read «Biblioteksbladet» [the journal of the Swedish Library Association] could have guessed that, too. An interview with Gerald Leitner which appeared in the said magazine two years ago started with the following preamble: «With dramatic language and Bill Gates’ money, the world’s libraries must be made to keep pace with the times. IFLA Secretary General Gerald Leitner is struggling with a library world where «hundreds of thousands» of librarians are reluctant to change.»

A pick from the interview:

«Biblioteksbladet: Are those who work at libraries laid back and in the absence of insight into the need for change? Leitner: -Many people undoubtedly have that attitude and that is perhaps one reason why we must use such strong words to make it clear that they must take part in this movement. Biblioteksbladet: «The movement» is above all the work with a common strategy for the world library, which began this year with the help of a ten-year financial support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which Gerald Leitner describes as a game changer.»

A game changer would be one that gives the game a new direction. And maybe even a new outcome.

What game?

The game about the future, one might answer. But whose future, should one then add.

The BMGF´s philanthropic contribution to the library field is of course small potatoes compared to its investments in the pharmaceutical industry, the mining industry and other important industries. The BMGF is also currently one of the largest funders of the World Health Organization. Here we are not talking about a meager million (compare the grants to IFLA) but about hundreds of millions. Thus, the Gates Foundation contributed $ 629 million, more than 14%, of the WHO’s entire budget in 2017 – something to keep in mind in these corona times.

Have Bill and Melinda Gates decided to save the world? That’s what it looks like. But of course they intend to do it in their own special way, based on their image of how the future should take shape.

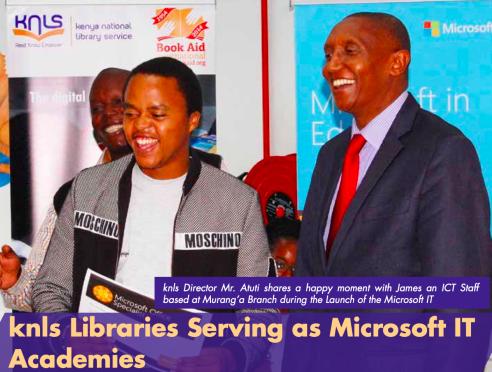

The fact that the BMFG´s philanthropic activities go hand in hand with the promotion of Microsoft’s business interest can hardly be denied.

An example of this, this time from the «library field» in Kenya. In its newsletter from July 2016, the Kenya Library Association talks about various operating grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Furthermore, we learn that Kenya National Library Service (KNLS) in collaboration with Microsoft has established Microsoft IT Academies in its public libraries and that teaching in these Microsoft IT academies consists of courses in the use of Microsoft’s Office software and the Windows operating system.

What is good for General Motors is good for America, said former GM chief Alfred P. Sloan. Which could always be doubted. As doubtful, of course, is whether what is good for Microsoft is good for Africa.

My intention with this blog post is to point out two problems, the first of which is as old as our civilization, while the second, as far as I understand, has no direct equivalent in the previous history of the human race. The first is the throughout history often very problematic dependence of the poor on the rich. The latter is a question of what E.F. Schumacher once called a refusal of consciousness, namely the refusal to awaken to consciousness about the nuclear threat to life on earth.

Don’t misunderstand me, it is not wrong to receive money from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to fund good library projects in different countries with a view to sustainable communities. The problem is how the IFLA (or individual library associations or libraries) should preserve their independence in relation to the donor. In the library world, this can be particularly difficult if the contributor’s business interests, as in this case, interfere with the recipient’s own area, that is, information technology. In short, the library should promote and use open operating systems and free software. But how does this go along with being financially dependent on Microsoft or any other of the IT industry’s giant companies? The example with Microsoft IT Academies in the public libraries of the Kenya National Library Services intends to show what an overly close collaboration between public libraries and private funds and companies may look like in the field.

Regarding IFLA’s in-depth collaboration with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in the preparation of a strategy for creating sustainable societies, the problem lies not least in the interpretation of the concept of sustainability.

One of the most important prerequisites for sustainable societies is that we stop the ongoing nuclear armaments and get rid of the nukes. But this fundamental point has for some reason not been included among the UN’s global goals for sustainable development, also known as Agenda 2030. The reason is, of course, that the nuclear weapons states, which also wish to support Agenda 2030, would not have agreed to incorporate the nuclear disarmament into the concept of sustainability. Therefore, the price for the unanimous adoption of the new UN Sustainable Developments Goals in the Agenda 2030 was an utterly skewed concept of the sustainable development.

IFLA has especially advocated for SDG 16 on Agenda 2030, which ironically has the heading «Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions». The irony is that in order to achieve peace, justice and strong institutions, one would have to steer the enormous resources that are today wasted on mass destruction systems, wars and military armaments towards a development that deserves to be called sustainable. But this is something that is completely overlooked in the official description of UN Development Goal 16.

And IFLA has still not raised the voice of the international library community in support of the UN Convention on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. (On this issue, see my previous blog entry The Library as Publisher in the Whole Wide World.)

Why?

I have to admit that I do not know or understand exactly why this is so. But I feel that the managment of IFLA management is afraid of clashing with its biggest individual financier through an independent stance on the nuclear issue.

However, the question is how long IFLA and BMGF can remain merry bedfellows. IFLA represents, or should at least represent, a peaceful and internationalist institution (the library) that is not affiliated with any of today’s militant nuclear states. I do not think the same can be said of BMGF, even though the director of Microsoft is no longer Bill Gates.

Just over a year ago, Microsoft – in fierce competition with Amazon – won the battle for a business contract with the US Department of Defense Pentagon. Under the contract, which is said to be worth at least $ 10 billion, Microsoft will expand and innovate Pentagon’s information technology. More specifically, it is about the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI), which is described as follows by the Pentagon:

«The DoD’s General Purpose Enterprise Cloud, also known as the Joint Enterprise Defense Infrastructure (JEDI) Cloud, is the initiative that will deploy foundational cloud technology, while leveraging commercial parity, to the entire Department, with a focus on where our military operates–from the homefront to the tactical edge. JEDI Cloud will provide fast, responsive, flexible, and adaptive cloud services to users at all classification levels. This initiative will create a foundation for efficient data sharing via its evolutionary cross domain solution, advanced data analytics capabilities, and a cutting edge cybersecurity posture for the Department of Defense.»

An article in the New York Times commented on the JEDI contract as follows:

The contract has an outsize importance because it is central to the Pentagon’s efforts to modernize its technology. Much of the military operates on 1980s and 1990s computer systems, and the Defense Department has spent billions of dollars trying to make them talk to one another.

Since Microsoft is an American business company, it is perhaps not particularly surprising that Microsoft is more than happy to undertake this JEDI contract, despite the fact that the United States is the world’s leading nuclear weapons state. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation hardly has anything against it either.

Until further notice.

Because eventually Microsoft and BMGF might have to change as well.

Since Agenda 2030 was adopted by the UN in 2015, something of great importance has happened. A clear majority of UN member states have negotiated and approved the Convention on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and approved it in July 2017. As of autumn 2020, a sufficient number of countries (> 50) have also ratified the Convention, which means that it will enter into force in January 2021. We have thus gained an important new international legal tool for promoting the sustainability of societies. From a legal point of view, nuclear possession, further development of nuclear weapons and threats with nuclear weapons will henceforth be violations of international law. The nuclear-weapon states and their military-industrial-academic complexes must also eventually comply with this law, although this will of course require further efforts. Or as an expert in the field writes writes:

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons makes a case that nuclear weapons are in fundamental conflict with basic humanitarian sensibilities and international law. If it is to ultimately be successful, this view will have to become the common sense of the world. – Zia Mian in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 30, 2020.

It is by being an institution of education and enlightenment, that is, by being true to themselves, that IFLA and the world librarians can make an important contribution and become a game changer. But then IFLA must dare to stand up for its cause, the library, whose existence and activities are a necessary condition for a kind of sustainable development that corresponds to «the common sense of the world».